LuSTRum has other meanings: MaRSh, SWaMP, WooD, FoReST; in short, places iLL-SuiTed for SeTTLement (another fine example of a contronym, a word with two opposed meanings). Talking about forests, let’s return briefly to the STaKe. In Akkadian, QiShTum means a forest, a BoSK. A forest is like the QuiVeR of a BoW, QeSheT in Hebrew, filled with wooden stakes. The stake appears in the Akkadian SanTaKKum, which is the cuneiform SiGN, the TRiaNGLe, i.e., the TRaCe left by the PoiNTed TiP of a STyLus in CLaY.

« ShaTa » with the idea of SeaSoN also appears in the Akkadian ShaTTum: a year, a moment in the year or ... a season, or in iShTu: a fixed moment (for instance in tablet V of the Enuma Elish), or a LaNDMaRK; landmark in SPaCe, but above all in TiMe, with the meaning of « SiNCe ».

This notion of landmark, of ReFeRence PoiNT, which we talked about at length in my previous video, is also present in iShTanum, the NoRTh, and ShuTum, the SouTh, just as it is in English (and French) with WeST (oueST), eaST (eST) or even the SePTentrion (from « The seven STaRs » in Latin). And as we're dealing with STaRs and wind roses, how can we not mention the goddess iShTaR, aSTaRTe, whose symbol was a star (« ShaTa »), with 6 or 8 points.

As a matter of fact, « ShaTa » as landmark is so fundamental in Akkadian language that it is found in the number « one », iShTen. It has also been preserved in Hebrew with SheTayim, which means « two », but is a dual « YiM » form of « ShaTa », the One.

This DuaL aspect refers to the TWo seasons, two being perceived as the DouBLe of oNe. Two seasons, but also two BuTToCks (SheT in Hebrew, Séant in French, aSS in English). And you know which asses I'm talking about! The asses of those stupid Pharisian linguists and anthropologists of course, which I won't stop kicking until they're finally thrown out of the temple of human knowledge.

Speaking of Pharisian linguists, thanks to « ShaTa »'s position in the semantic field of the seasonal FeSTival, I can correct one of their many silly ideas; that according to which, if a long word looks like a short word, the first systematically stems from the second. Having trouble following me? You'll get it in a minute.

Many words feature this « ShaTa STeM »: FaSTuous, FeaST, GeSTure, JuST, VaST, ViSiT, ChaSTe. All these words derive from identical Latin words FaSTus, FeSTum, GeSTus, JuSTus, VaSTus, ViSiTo, CaSTus. Apart from GeSTus (derived from GeRo) and CaSTus (which etymology is unclear), the etymologies of these words point to them deriving from a simpler « Sha stem »; for instance, FaS for FaSTus and FeSTum, JuS for JuSTus, VaS for VaSTus, and ViSo for ViSiTo.

In all these words, the suffix « ShaTa » disappears and only « Sha » remains. But isn’t it strange that all these words relate to the immense semantic field of CoMMeNSality and iNSTiTutions? Well, truly I say to you, it's the short form, without « Ta », which is a derivative of the long form with « ShaTa », and not the other way around, as commonly believed! In practical terms, FaS comes from FaSTus, not the reverse.

This phenomenon is also at play in the verb SeRo, which means to KNoT and to LoCk, as well as, weirdly enough, to SoW. We already saw the first meaning of knot a year ago, in my first video on orality, « Écoute (Israël) la série des sermons du sire disert », about ShaRShaR, the ChaiN and the STiTChed RhaPSoDy. As for the verb « to sow », its meaning is often associated with SaTus (sowing), SaTivus (that which is cultivated, sown), related of course to SaTio, which means both SaTieTy and SeaSoN (including the sowing season in Neolithic times).

However, if sowing doesn't relate to knotting, it's because it's not SaTus that derives from SeRo, but SeRo that has taken on the meaning of SaTus. This phenomenon also occurs in Old French with DéCheT (TRaSh) giving birth to the verb DéChoir (to deprive of), and the infinitive éChoir (to FaLL to, to fall Due) coming from éCheT.

Of course, this isn't an absolute, and sometimes the radical is indeed the original form, for example with Suo, (to STiTCh), and SuTus (what is stitched) - remember, SheTy is also the Hebrew word for the WaRP (la ChaîNe in French). I'll come back shortly to WeaVing, but above all to this foundational Paleolithic inversion between object and action, which is quite counter-intuitive for us, as we’d rather think of ourselves primarily as SuBJeCTs perceiving oBJeCTs.

Anyway, I imagine you're starting to grasp the institutional roots of « ShaTa », which I discussed at length in my previous video. Patiently, step by step, millennium after millennium, the iNSTiTutions that STRuCTuRe human cooperation were WoVen during those times of GaTheRing and SeTTLing (weaving again!), times when RhaPSoDies and FaMiLy Ties were woven, as well as the first CLoThes and JeWeLRy, which I'll come back to in future videos.

The STaKe, PLaNTed in a hole and wedged with STuFF, was the archetype of the settling process. Planting a stake is indeed the very first STaGe (or STeP) in the CoNSTRuCtion of the ancient BooTh I alluded to: the STaRT (another fine example of phono-semantic fusion « ShaTa-Ra »), and its twin, SToP.

The booth is a cherished childhood memory inhabiting the depth of our soul, whether we BuiLt it in a TRee, in our BeDRooMs or tucked away in our parent's BeDSheeTs. This primordial booth is also the fundamental archetype evoked in Genesis when QayiN, guilt-stricken by the murder of HaBeL, is addressed by God's compassionate words: « haLoʔ ʔiM teyṬyB SheʔeT, veʔiM Loʔ teyṬyB, laPeTaḤ ḥaṬaʔT RoBeTs » « If you improve, you will STRaiGhTen up », SheʔeT, « otherwise Sin lurks at the door (of your booth) ». Now that you're getting familiar with Paleolithic culture, you understand how far this sentence roots back to...

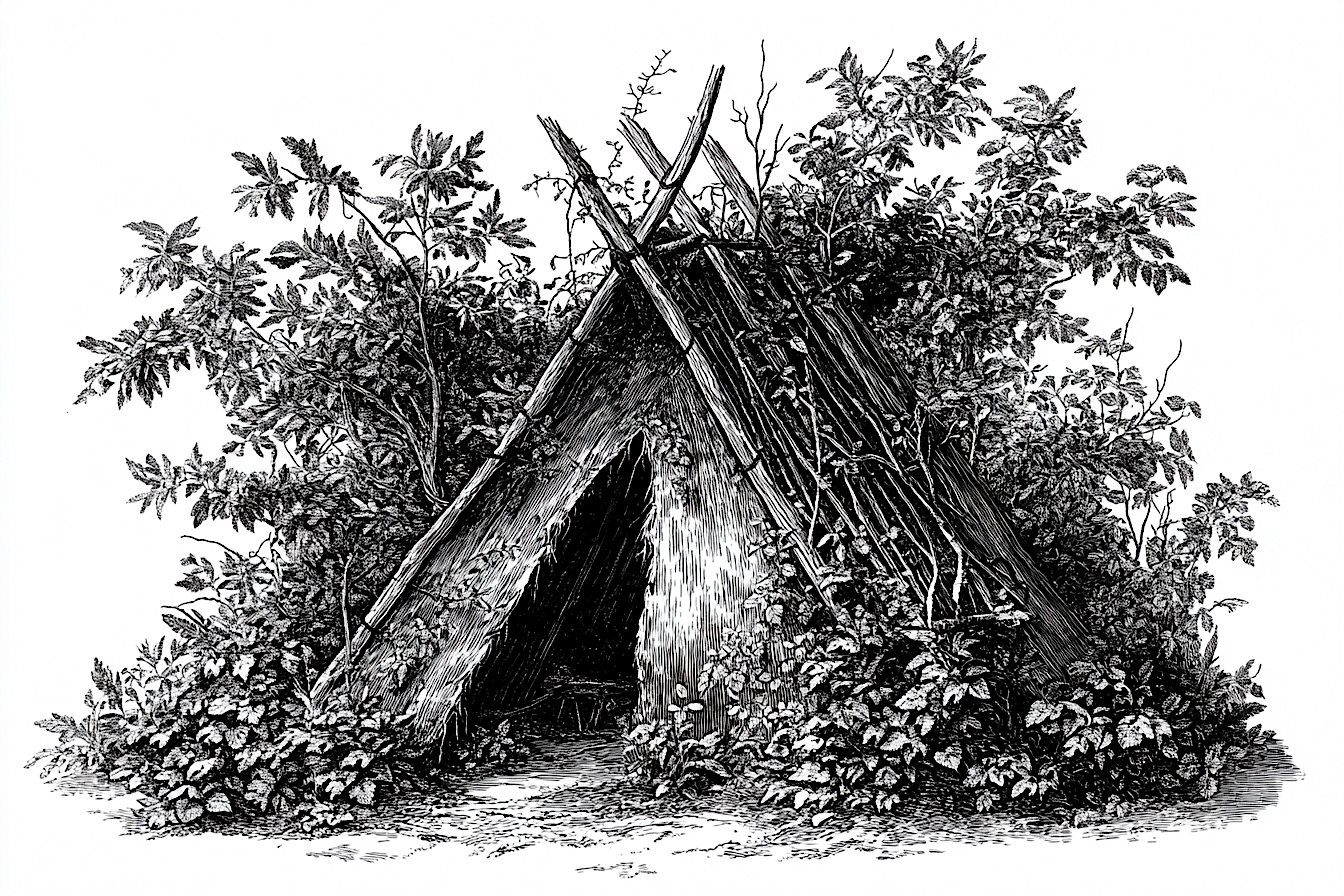

The Greeks also recalled this primordial booth, as the great Gabriel Camps wonderfully recounts in his « Introduction à la préhistoire »; a book written 40 years ago, but which remains very much up to date. Page 30, he explains that, for Ovid, the great Roman poet and mythologist: « The first step towards decline is the Silver Age, when the SeaSoNs appear and replace the everlasting spring. Adverse weather forces humans to seek SheLTeR. Ovid shows them taking refuge in CaVes, then BuiLDing HuTs from ReeDs ».

A little further on, on page 104: « WooD has probably been used in the CoNSTRuCtion of SheLTeRs and then huts for as long as weapons or instruments have been manufactured. The idea of interWeaVing BRaNChes to make a shelter is so primitive that it can be assumed to date back to the dawn of humankind ».

This book is a gold mine for my fellow Paleolithic enthusiasts. It taught me a lot, including that, not so long ago, FLiNTs and BiFaCes discovered in fields were thought to have been shaped by LiGhTning (in Italy flints were called « saetta » because of their PoiNTed shape).

Coming back to huts, the superstar of Paleolithic huts is in France, near Nice, at Terra Amata; a site where traces of a DWeLLing built under huts have been found, dating back - brace yourselves - to 400,000 years ago, well before Homo Sapiens, and even well before Neanderthal. This dwelling is thought to have been built by our common ancestor, Homo Erectus, who appeared around 2 million years ago, was the first to colonize the Eurasian continent over 1 million years ago and disappeared 110,000 years ago on the island of Java in Indonesia.