But when one tranches, one necessarily measures : MéTRoN in Greek, where MeTeR comes from, and LiTRa, which gave us the LiTeR to measure volumes. And whoever measures, counts the PaRTs, starting with two: the one and the « other », from the Latin aLTeR and which the Greeks call éTéRoS. heTeRo- is the other.

I'll have more to say about these Latin -TeR suffixes in my next video, but I can already mention uTeR which means one of the two, from which « autre » (other) derives, as well as the French « En ouTRe » (furthermore). There's also eNTRe (between in French) and ConTRe (CounTeR), from the Latin iNTeR and ConTRa - with the same idea of separation into two parts.

But when we CuT, we don't just cut in two, of course, we also cut in three parts - to make thirds or TieRS - and in QuaTRe (French for four) to make QuaRTeRs (with a nice metathesis here between the R and the T). The Greek word for four is TéSSaRéS, but the original form was probably TéTTaRéS, which we find in the prefix TéTRa-.

A wide number of words use TRi- and TeTRa- as prefixes, but one stands out: TRiBe, found in terms related to sharing such as aTTRiBuTe, DiSTRiBuTe, or TRiBuTe.

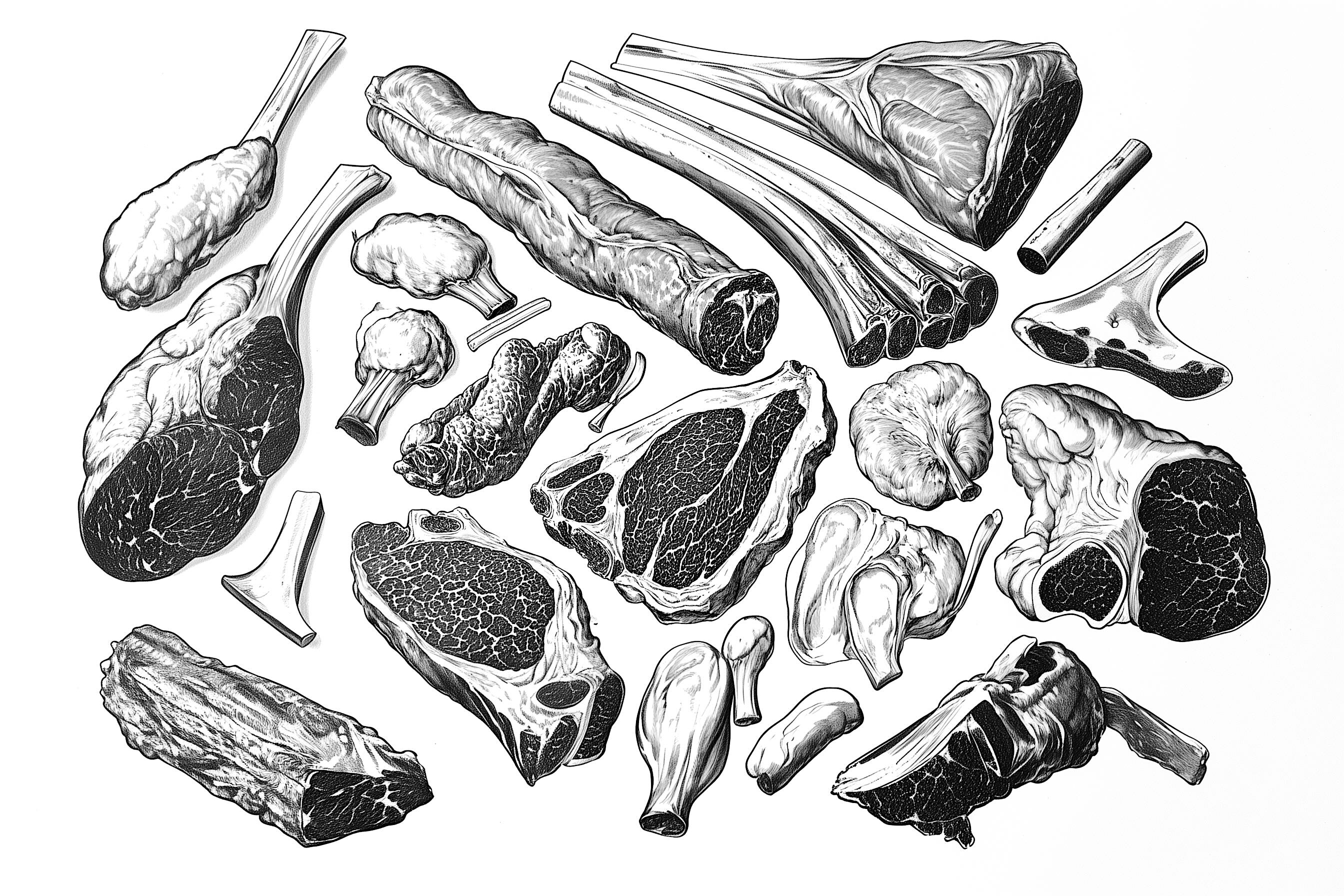

The tribe is the social body that is PaRTed (or that one PaRTaKes in) in the context of PaRTing the hunt - but of course, not necessarily in threes, contrary to popular belief. The words « Trois / Tri- » (three) and « Quatre / Tetra- » (four) are important, not because of the quantities they represent, nor because they evoke the Christian symbols of the TRiNiTy and the cross, but because they embody the act of sharing.

To be cut up, a body has to be big. That's why slicing is related to the concepts of abundance and multitude. In French, we have the adverbs TRèS (very) and TRoP, (too much/many) from which derive TRouPe (TRooPs), and TRouPeau (herd) : groups containing a high number of individuals. There's also a very important Arabic adverb, KeTYR, which means a lot. KeTYR, KeTYR, KeTYR ! A lots, a lot, a lot ! found in the first name KaWÇaR, which means abundance.

KeTYR is very interesting, because in Arabic KiTR or KaTR is the dromedary's hump, whereas in Hebrew KeTeR means the CRoWN, the capital or the verb « to SuRRouND ». Could it be that KeTeR, the crown in Hebrew, has something to do with that prized part of the dromedary, the fatty hump that one slices, KaReT? No need to get ahead of ourselves, but let's keep this in mind...

In the meantime, Egyptian has, of course, ITeRuW, the Nile. The river that represented the abundance and wealth that gave birth to Egyptian civilization has been erroneously linkened by some to YeʔoR, the river in Hebrew. YeʔoR is « Ra » in the sense of flowing (I also forgot to mention this in my last video). ITeRuW is « Ta Ra » with the meaning of abundance.

As a matter of fact, in Egyptian TeR is the season, the time, and has probably more to do with the abundance brought by the floods of the Nile, ITeRuW, than with sharing. As you must have gathered by now, Hebrew is much closer to Latin and Greek than Egyptian. But we'll soon come back to this not so close relationship between Egyptian, Hebrew, Greek and Latin; which had serious historical consequences, not only during Neolithic times, but especially during Paleolithic ages...

Let’s get back to the carcass. By dint of tranching and slicing it, we end up TRiTuRaTing it - i.e. turning it to pieces : TaRTaR in Hebrew. triturate comes from TeRo, a very important verb in Latin, found in TRaSh, DeTRiment, and in French TRier (to SoRT). TeRo means to rub the SKiN, TeRGum in Latin, which also means the back of the body, and appears in the verb TeRGeo, meaning to scrub, to clean, featured in DeTeRGent.

The Greek equivalent of TeRo is TéiRô; but the same allussion to rubbing is found in the verb TRôGô : to gnaw, or even in French and English with the gnawing RaTs and TeRMiTes. Most of all, we find it in TRiBô, which also means to rub, and from which I believe the French TRaVaiL (work), with its much-debated etymology, derives.

Indeed, our ancestors spent quite some time rubbing hides, especially in Europe at the end of the last Ice Age. In the Palaeolithic, rubbing hides was vital as they turned into shelter, clothing and soft containers. But for this, hides had to become spotless and shiny! And if working (travailler in French) is TiRing, TaRDus in Latin, it's because for at least forty thousand years, working has meant… toiling and rubbing – much TRaVaiLs indeed.

Unfortunately, rubbing too much can create TeaRs or TRous (HoLes in French), from the Greek TRyPa or TRyMè, which also means to exhaust. And this is when it becomes TeRRible, from the Latin TeRReo or the Greek TRéô: to be scared. Of course, since a TeaRed HiDe not only looks bad, but also lets in the rain and the cold.

More importantly, a teared hide is terrible because it reminds you of a wound, a TRauMa. Remember getting a SCRaTCh as a child, how the sight of the tear in your physical integrity terrified you and made you burst into TeaRs. It was so sad, TRiSTe in French. And in the Paleolithic era, people often pierced their skin while flintknapping - but I'll come back to this in my next video. Sometimes, they even drilled holes in people’s skulls; a practice, more than 10,000 years old, known as TRePaNNing.

Yes, a tear, a LaiR (aNTRe in French), is scary; it makes you TReMBLe, from the Latin TReMo and the Greek TRéMô. This is also found in Hebrew with RaTaT and RaTaʕ meaning to tremble, to be FRiGhTened, and with RaTaḥ meaning to tremble or to boil (note the Ḥa of Hot), or RaTah which, conversely, means to be lenient. A TyRaNT, TyRaNNoS, is one who rules with FeaR, by being TRuCuLent, from TRuX which means wild, FieRCe in Latin.

Lastly, in English we find the meaning of the TeaR in many « Ta Ra » words like ThRouGh, DRiLL, ThRoW, ThReaD or ThRiLL. In Egyptian, this meaning is only found in SeReT, a ThoRN - but as you can see, the harvest here is again rather scant.